The idea for A Journey Through Literary America came to me in January of 2008 in Kawasaki, Japan (near Tokyo), where I was visiting my wife’s family.

On the plane on the way over, I had devoured American Pastoral by Philip Roth. The book is narrated by one of Roth’s literary alter egos, Nathan Zuckerman, but it mostly concerns itself with the life of someone he grew up worshiping: one of the greatest athletes that Zuckerman’s Jewish Newark neighborhood of Weequahic had ever known: “Swede” Levov. So named because he looked so Swedish rather than Jewish, the Swede had married a Miss New Jersey (Catholic, much to the horror of his parents) and waved goodbye to a promising baseball career in order to take over his father’s glove factory in Newark.

Weequahic is not only Nathan Zuckerman’s stomping ground but also the neighborhood where Philip Roth grew up. One might use the term “predominantly Jewish” nowadays for how it was, in order to be respectful of other races that might have lived there, but back then I am sure it was known simply as the Jewish neighborhood. That is, solidly, squarely, any way you slice it—like a Snickers bar is packed with peanuts—Jewish. That was then. Nowadays, the neighborhood is quite mixed.

Photo: Thomas Hummel

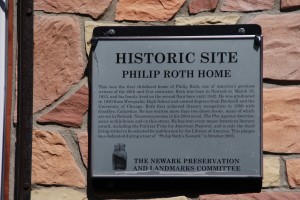

There is a plaque on the house Roth grew up in, and a nearby intersection is named “Philip Roth Plaza,” The term seems misleading to me. I usually think of a plaza as a place to gather. I wouldn’t recommend gathering in the middle of a Newark intersection.

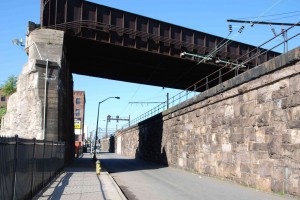

It is proper of Newark to honor Roth with at least an intersection, because some of his best writing is about Newark, starting with Portnoy’s Complaint (1969)—the novel that made him a household name and suggested a heretofore unheard-of (in literature anyway) use of liver for a sex-crazed boy. American Pastoral (1997) features vivid descriptions of Newark, from World War II through the Newark Riots in the 1960’s, and beyond. It sparked something in me back in 2008. I remember, for example, marking the passage where Roth writes about the Newark viaduct, “the Swede’s first encounter with the manmade sublime that divides and dwarfs. (American Pastoral, 220).” As Roth went on to say:

“That grim fortification was the city’s Chinese wall, brownstone boulders piled twenty feet high, strung out for more than a mile and intersected only by half a dozen foul underpasses. Along this forsaken street, as ominous now as any street in any ruined city in America, was a reptilian length of unguarded wall barren even of graffiti. But for the wilted weeds that managed to put forth in wiry clumps where the mortar was cracked and washed away, the viaduct wall was barren of everything except the affirmation of a weary industrial city’s prolonged and triumphant struggle to monumentalize its ugliness.” (p. 219)

Photo: Thomas Hummel

What was so special about American Pastoral that it lit the fuse for a book? I think Roth did it for me by the way he attached importance to surroundings. In one passage he writes:

“Perhaps by definition a neighborhood is the place to which a child spontaneously gives undivided attention; that’s the unfiltered way meaning comes to children, just flowing off the surfaces of things.” (p. 43).

As Samuel Johnson once said, “The true art of memory is the art of attention.” And what Roth created—and sold me on—was a truly artful job of memory and art. Through a preponderance of evidence, real and imagined, he brought the particular character of the city of Newark to life on the printed page.

After reading American Pastoral, I wanted to go to Newark with my brother, who lives in New York City and is always up for poking around a down-at-the-mouth area, and photograph the Viaduct. Put images to Philip Roth’s text. Part of the spark, then, came because I felt sure that the Viaduct was still there, and as Roth had described it. If I had to follow the river of this book’s inspiration all the way to its headwaters, this would be it: the little spring at which it all started was the idea of capturing places in pictures that great authors have described.

My original intent was to write text that was more like what you would find in a guidebook. Lively, yes, but mostly spare and functional. A side dish. And then what happened is that fervor of the writers gripped me. A side dish wasn’t good enough. I needed to do them justice, as much as I could. And at times, I felt as though I were competing with them. I did so with a pure pleasure in the sport of it, as I might get from leaping to catch a baseball, or a running down a fly ball.

I sometimes think that in 2007 I was inching my way towards an early senescence. I got tremendously tired at night. There was hardly a movie that I didn’t fall asleep in the middle of. I still had the lifelong desire to write but the novel I was working on sometimes put me to sleep while writing it. That fog has now lifted. Willa Cather once claimed that in order to write well she had to “get up feeling 13 years old and all set for a picnic.” Since I started working on A Journey Through Literary America, I have gotten up feeling, well, not that good but with a relish for life and for writing that I think must be akin to what Cather felt. TRH

Author’s note: capturing the Viaduct the way that Roth described it turned out to be nearly impossible—for me anyway. Tamra Dempsey, who took all the photographs for this book, had more success than I. But the best picture of it that I have seen remains the picture of it that Roth created, using words, in his book.