I am now reading a book I picked up many years ago called New Burlington. It caught my eye because I am from a Burlington—Burlington, Vermont. But this book was about New Burlington, Ohio, a town that has been soaking under the Caesar Creek Reservoir waters for over thirty years. The author, John Baskin, a reporter for a city paper, came to New Burlington in the early 1970’s, was told that it had been condemned for the purposes of making a reservoir, and decided to move in to record the town’s last year. “I have come to live in New Burlington’s last farm house, surrounded by white brick and clean silence. I have come here to understand its death, my life. Nothing is revealed.”

New Burlington was like a lot of other villages. It had been settled by people pushing west. Its original buildings were solid mortise and tenon construction. Built so they wouldn’t blow down. There were town characters. And the stories of those characters were handed down from one generation to the next for edification and enjoyment. When New Burlington was settled, it was possible to walk from there to Chicago without ever leaving the forest. Electricity came slow to the community, as did most change. By the time Baskin happened upon it, the two village blacksmiths were still alive—men with big scars on their fronts from not wearing the proper equipment while using hot metal, man who looked back fondly on making wagon wheels and shoeing horses.

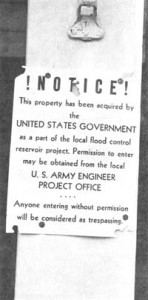

As Baskin wrote in his original introduction (the book later came out as a Norton paperback), he began the project with a great deal of sentiment, seeing the Army Corps of Engineers as the villains and the town as the victim. He wound up writing himself out of the narrative. It became a book about the residents in the town who, much like the characters that populated the crossroads of and hollows near the blue highways of William Least Heat Moon’s book, were characters in their own right. They were Americans whose memories and way of life seemed to stretch back beyond the turn of the last century, to a vanishing point that seems almost completely separated from the way we live today in the United States.

“It is likely,” Baskin wrote, “the reader will wish to look at New Burlington as a history. When I think of history, I think of a lady named Abigail Winas who said, ‘History is a drunk in the snow with his feet sticking out.’ I think of New Burlington as a book of stories and voices in which the characters ponder some of their time on earth.”

The kind of existence Baskin describes slowly dying out in New Burlington before it gets flooded away seems to me to be part and parcel of what poet, novelist, and essayist Wendell Berry has been advocating for many years: the rhythms of the small town life, wisdom passed down, the long memory. Berry, who was born in the Bluegrass State, obtained an M.A. in English from the University of Kentucky, then studied with Wallace Stegner at Stanford and briefly made the rounds of academia before buying a farm in Henry County, Kentucky, not far from his family’s roots.

He’s been living there since 1965 and has produced prolifically, damning the corporatization and industrialization of agriculture and arguing for a more New Burlington way of life. In some ways, the “buy local” movement is a commodified version of his exhortations. In fact, most corporate efforts or missions to live more like Berry preaches (and they are ever increasing) come out sounding pretty commodified, full of buzzwords—a trap that he has never fallen into. Berry is a one man movement. He also has the poetic gift. Below are the opening three stanzas of “In a Motel Parking Lot, Thinking of Mr. Williams,” a poem that seems to express what those old residents of New Burlington pretty much took for granted:

The poem is important, but

not more than the people

whose survival it serves,

one of the necessities, so they may

speak what is true, and have

the patience for beauty: the weighted

grainfield, the shady street,

the well-laid stone and the changing tree

whose branches spread above.

As Baskin wrote of New Burlington in the nineteenth century: “Buildings rise from the landscape like gigantic blooms of wood and stone. Their weight and symmetry are pleasing to the eye. Such building, for a time, may be seen as piety…Even the barns of New Burlington, like the architecture of ancient churches, had buttresses, arches, naves, and aisles.”

Same feeling as Berry’s poem. Same grave and respectful tone.

And here I must confess to somewhat of a feeling of failure: not only because I do not live as the New Burlingtonians lived, and the people off the blue highways lived, and Wendell Berry lives, but also because when I set out on my journey into literary America, I was hoping to come across those people. I set out thinking I would find the “salt of the earth” America and Americans that are rumored to be out there around the long curves on the blue highways, the ones who have the patience for beauty: the weighted graveyard, the well-laid stone.

I didn’t find them.

I cannot say with a certainty that they are there, though I believe they still exist.

I must come to terms with the fact that, in the process of doing the research for this book, I had very little time to meander around the back roads. I must also make peace with the fact that I am not going to (like Least Heat Moon) wander into a bar and strike up a conversation with the person on the next stool, who might somehow tie my entire quest together with a few well-spoken lines. I need to get the lay of the land before I feel I know what is true and what isn’t. Time did not allow that. Furthermore, visiting the rarefied air of Concord, Massachusetts, for example, is not likely to put me in touch with pithy Yankee wordsmiths (though it once served exactly that purpose for Emerson). I must also confront a bias of my own (that I am now noticing) that “authentic” somehow equals countrified. It doesn’t. Full-fledged authentic Americans can be found in large cities, medium cities, towns, villages.

Having professed a feeling of failure, though, I must consider the achievement of the book itself. A Journey Through Literary America is a 304-page narrative, in picture and words, of the American experience. It features a range of voices. It reaches back to the furthest regions of America’s literary memory and carries forward into the present. It gets off the interstates and onto the less traveled roads, travels north and south, east and west, by ox cart, riverboat, train, automobile, on foot. After finishing the book I feel somehow that my own memory has been furnished—with recollections of events from previous decades and centuries. This happens when one immerses oneself in narrative.

I should also say this: those “authentic voices” I went out there to find are probably not the same ones who are going to continue the American literary narrative. Some writer, at some remove from them, is going to do that. And, while finding America in the back roads and back alleys is worthy of a quest, the experiences that will probably best equip us to move forward into this new and already troubled century are the ones we can get from America’s great writers and artists.

We are often reminded, especially now, in uncertain times, of America’s great ingenuity and positive spirit, of how the country has rallied to face down so many challenges and obstacles. May I say that many of the people who regularly trot out these palliatives have only the vaguest notion of the details underlying the supposed achievements? I am all for pep talks. But not substance-free ones. Not the creeds outworn. I am more and more convinced that the tide of history is what produces great changes. We had better study the tides and how they affected those who came before us.

Back now to “In a Motel Parking Lot, Thinking of Mr. Williams,” to the closing stanzas:

To remember,

to hear and remember, is to stop

and walk on again

to a livelier, surer measure.

It is dangerous

to remember the past only

for its own sake, dangerous

to deliver a message

you did not get.

TRH