On February 7, 2010 in Sauk Centre, Minnesota, it is 18 degrees but “feels like 8 degrees” according to Weather.com. This is not so different from this day 125 years ago when Sinclair Lewis was born. It was bitter cold in that day in Sauk Centre (population 2,800). Ice glittered on the 30 lakes that dotted the landscape around the town. The wagon ruts down the mud of Main Street were frozen as solid as the iron-clad wheels that had made them, the ridges at the top brittle and crunchy like exceedingly stale chocolate. The steam from the locomotive of the Great Northern coming into town hung over the rails, too frigid to billow. On that day a baby named Harry Sinclair Lewis was born. No one knows where the Harry came from. Sinclair, the name he adopted as his nom de plume was the surname of a Wisconsin dentist who was a good friend of Lewis’s father.

It had only been 24 years since the first white child was born in the former Indian territory. Harry Sinclair Lewis’ parents did not take his convulsive sobbing any more seriously than they would take any other baby’s. Infants find conditions to be unfamiliar and harsh, but they adjust, grow into little children and naturally find their way in the world. Little did they know that young Harry would find life to be such a trial, that he would eventually make them all famous—or how little they would like that fame.

His father was one of the two doctors in town: the stiff and stern one, the one of whom it was said you could set your clocks by. He left his home promptly at 7 am to walk down Main Street to his office. He would leave the office at 11:30 on the dot to go home for lunch and change his hat—always the same hats every day, always the same peg for each one. Lewis’s natural mother died when he was still young. Dr. Lewis promptly married again (after all, he had sons to raise) and the second marriage proved beneficial for young Sinclair. She was as good as a natural mother to him, and a buffer against his father, whom Lewis later pilloried (along with the town itself) in his breakthrough novel of Main Street.

Main Street, published in 1920, lifted a corner of the roof off small-town American life so that one could peep inside and see its inner workings. He wrote from experience. His fictionalized town of Gopher Prairie was easily recognizable as Sauk Centre—and a thousand other towns like it along the American expanse. This is how Carol Kennicott, Main Street’s sprited protagonist saw it when she arrived for the first time by train:

“The huddled low wooden houses broke the plains scarcely more than would a hazel thicket. The fields swept up to it, past it. It was unprotected and unprotecting; there was no dignity in it and no hope of greatness. Only the tall red grain elevator and a few tinny church steeples rose from the mass. It was a frontier camp. It was not a place to live in, not possibly, not conceivably.”

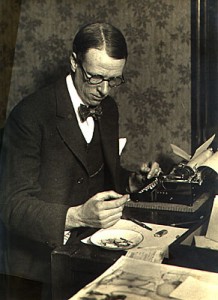

Sinclair Lewis’s success following Main Street could be held up as a triumph of that much heralded American virtue of stick-to-it-iveness. As he was fond of saying: “The art of writing is the art of applying the seat of your pants to the seat of your chair.” He had an entire file of plots (some of which he sold to Jack London—and some of which London paid for), he wrote five novels before his breakthrough novel Main Street, the novel that many mark as the beginning of his career. But though he spent a lot of time writing, he did not spend much time in any one place. His was a restless life. He worked on a cattle boat, sought work in Panama, did janitorial work at Upton Sinclair’s experimental community, and acted as handyman at a writers commune in Carmel (where he met Jack London) before he achieved fame. After he achieved it he continued to move from place to place to do research.

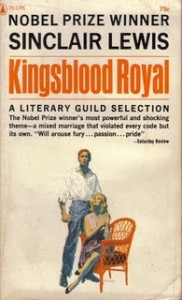

This being Black History Month, it is worthwhile noting that he wrote a novel called Kingsblood Royal about a white man who finds out he’s part black.  He also wrote a novel about the takeover of the United States by a populist leader who turns it into a military state (this novel was repackaged and re-issued during George W. Bush’s presidency). I know of no American writer who has surpassed Sinclair Lewis for pure lacerating satire and dead-on dialogue. As time passes, I wonder if he will yet be looked at as an interpreter of our American spirit or whether, as the nation evolves, his works will come to be seen as time capsules of an American era now part of history.

He also wrote a novel about the takeover of the United States by a populist leader who turns it into a military state (this novel was repackaged and re-issued during George W. Bush’s presidency). I know of no American writer who has surpassed Sinclair Lewis for pure lacerating satire and dead-on dialogue. As time passes, I wonder if he will yet be looked at as an interpreter of our American spirit or whether, as the nation evolves, his works will come to be seen as time capsules of an American era now part of history.

TRH