I inherited the estimate from the soon-to-be departing production assistant, Angela. It was a quote for 10,000 copies and about $100,000. Not small potatoes. The client name was Control Bureau. Well, ok. The contact’s name was “Ximena” which I pronounced to myself as “Eximena” until I finally spoke to her and understood her name was pronounced “Himayna.” The book project was named Dictionary ABCDF and I kept thinking that someone had left out a vowel. I took the estimate folder with few expectations. The biggest jobs are always the hardest to get, and this one, for a thousand-page book, seemed destined to fall by the wayside.

After a few weeks of minimal tending, the project suddenly sprang to life. The people from the Control Bureau said they wanted to come to LA and pay us a visit. They came and stayed the entire day. Within the first few minutes I had learned that the “DF” of ABCDF was “Distrito Federal” – the official name of Mexico City. ABCDF was to be a picture dictionary of beloved things in Mexico City. I also learned that these visitors from Mexico City were unlike any other clients I had ever had. The ringleader was the red haired Cristina, who spoke broken English so quick and colorful that she had a fluency all her own. Then there was Jeronimo (pronounced “Heronimo”). He bore little resemblance to the Indian warrior. Mild mannered, but insistent, he was a photographer, gardener, and artist, and friend of Cristina. Ximena, (whose mother happens to be a famous photographer of the Luchadors – the famous masked Mexican wrestlers of Lucha Libre) had been called in for her production and design expertise. And also, it seems, for her calm under fire. Ximena had plenty of passion for the project. But it didn’t, as in Cristina’s case, display itself in a shower of sparks. Ximena’s intensity was almost like a dispassion; I never saw her raise her voice or even deviate much from her charming though strident tone (in Mexico the two adjectives are not mutually exclusive). The three of them were young, bright, talented, international.

The project arose out of a dream Cristina had had about making a book. Her dream about a book took the form of a dictionary after someone in the group came up with the title. Sparks flew. In a short time, the group (there were many other key participants besides the three I have mentioned, all of them young) settled on hundreds of words. “Before such a quantity of fortuitous and aleatory information,” Cristina wrote in her introduction, “the free and playful association of ideas and images found in Mexico City became the ideal motor [for the dictionary venture].” She went on: “The book is a collective exercise to discover and try to understand the sundry affection that this city inspires in its most mysterious, intimate, and devoted aspects.”

Toppan Printing Company became part of the venture because we had printed, and still do, many books for the Mexican market. Mexican publishers often produce books with higher production values (finer cloth, paper, and often artwork) than American publishers. Many Mexican art books are sponsored by big companies in Mexico, which give a portion of the books away at Christmas. The books are usually on a patriotic theme, whether it be flora and fauna of Mexico, or crafts, or other products. Not only do the sponsors demand the best but the designers seem to have been raised to demand the very best, too. In this way, Mexico is very different from the United States, where unit price is such a big issue and few big companies sponsor books.

It also seems nearly all of the designers and publishers in Mexico City know each other or are only a few degrees of separation removed. Coincidentally or not, nearly all of them have some European heritage. We had been recommended to The Control Bureau by a publisher, and bibliophile, who, at the time, printed all of his art books at our plant in Tokyo—one of the elite printing plants in the world. At the time, when the exchange rate was more favorable than it is now, it was also pretty reasonable to print there—if you wanted the very best quality that could be afforded.

I had no idea what I was in for. The thousand-page book became a 1,500 page book. The quantity became 15,000 copies. Not only that: the Control Bureau wanted a cover that was like red velvet, a carton with a handle, a lens that had an image on it that moved (a flip lens, or lenticular lens). They wanted a CD. They wanted a clear plastic jacket for some copies. They wanted three bookmark ribbons. They wanted the finest paper, but thin. They were asking for the moon. But such a fact never made them blink. It was, after all, a dream project.

Remarkably, every time I forwarded these seemingly impossible requests to Tokyo (the schedule was another issue, as were the many background colors that needed to be reproduced, nearly exactly, in the book), Toppan Tokyo came back with a solution.

At the time, I was carrying on a clandestine romance with the young woman in Tokyo who handled the projects of Toppan Los Angeles (we felt sure that revealing the relationship would either break some rule or protocol, so we told no one). Her mentor was a Mr. Takahashi—hard drinking, hard working, of limited English vocabulary. Mr. Takahashi helped her negotiate that man’s world of printing, and she did a fine job of negotiating it herself. The book grew in size and cost but she, and the shadowy behind-the-scenes figure of Takahashi San, never lost control.

It is somewhat hard to describe what is contained in the book. I always say it is a picture dictionary. But that never seems to get the point across. DICTIONARY ABCDF concerns itself with things that appeared in everyday Mexico City. Things that, if you grew up there, would seem absolutely familiar and if you grew up in the United States, for example would seem utterly foreign—like the way the trees trunks are painted white from the ground to about a meter high, or the way that tortillas are made by machine. There is a page full of Mexico City manhole covers, a page full of the Volkswagen vehicles that preceded the Volkswagen bus—called Combis. There are many photos of Volkswagen bugs which were, at that time, still being manufactured in Mexico and were still the mainstays of the unsanctioned taxi fleets in Mexico City. There are 5 pages worth of mobiliano—or furniture. Looking at it now, I realize how even the plastic furniture in Mexico has a certain look that it doesn’t have here. ABCDF contains a glossary at the back that gives the meanings of the words ands pictures in Spanish and in English.

I had been to Mexico City once, before the book, and I had taken away the (shallow and ultimately wrong) impression that it was kind of like Los Angeles: sprawled out, with many low-slung buildings, bright colors. There were a lot of carts selling juice—or jugo, just as there are in Los Angeles. There were streets full of jacaranda trees, with that strong blue-purple hue that seems so perfect to me. The first time I am in a big city, most of it winds up being a blur. And Mexico City was no exception, especially since, on the advice of our clients in Mexico City, my boss at the time and I had hired a car and driver so as to avoid being kidnapped or mugged or murdered. We saw the city from the back seat of a black Lincoln Continental.

I went to Mexico City for the second time in my life for ABCDF. And this time, the city was alive to me because of the images I had seen in the book. (The electric feeling of the city was immeasurably enhanced by the fact that Rika, the clandestine girlfriend who I am now married to, was also sent from Tokyo to Mexico City for the purpose of picking up an urgent batch of proofs). That second trip, I kept seeing things that were in the book: a chain of stores named “Suburbia”, the fire breathers who performed by blowing flames out of their mouths at the stop lights, the brooms that were made of real branches and looked like witches’ brooms. Rika and I stayed in the Zona Rosa, a somewhat dubious tourist zone. But we spent 95% of our waking hours at the Control Bureau.

Volcanoes: I had hardly noticed the volcanoes that surround Mexico City the first time I went. That second time I noticed them. They seem to be the reference points that the city dwellers mark their existence by—much like Mount Fuji in Japan. The entry for volcanoes in ABC DF includes a poem:

Visión de los Volcanes

But there are days when a breath

throws open our windows

blows down the clothes hung out on skyscrapers

lifts winged cottons

white snakes

and denudes a breast that lifts up

its point of light

and its congealed lump of milk.

Today is not yesterday

yet the volcanoes still astonish us.

– José Ángel Leya,

The more you probe in ABCDF the more you find. The opportunity remains for some travel writer to do a piece on exploring The Distrito Federal with the ABCDF as guidebook (after all, it even comes with a carrying case). I was fascinated by the Xólotl, or tiger salamander. “Not content with creating a being that resembles a small monster,” the entry reads, “…Mother Nature gave it another two features that turned it into an enigmatic, almost magical being: it is able to regenerate its nervous system, retina, heart, or cerebellum. At the same time, the tiger salamander can be said to be the Dorian Gray of animals: it is one of the few amphibians that does not metamorphose. It reaches adulthood without altering its youthful shape, a phenomenon known as neoteny.”

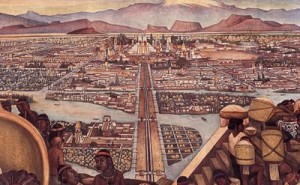

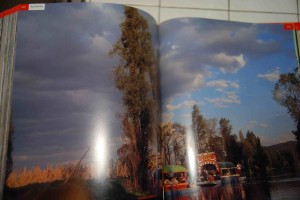

The X’s, though few, are rewarding. Also in that section is Xochimilco (which I never in a million years could have figured out how to pronounce), a remnant of the lake and canal network of the ancient civilization around Mexico City. The valley where Mexico City currently stands was once full of lakes. Settlements were built on those shallow lakes in the form of islands, and canals became the byways. The city of Tenochtitlán was built on an island on the western shore of Lake Texcoco. Seeing the massive lake city for the first time, the soldiers accompanying Hernando Cortez wondered if they were dreaming. As Diego Rivera’s murals in the Palacio National, on the east size of the Zócalo (which also has an entry in ABC DF) show, the unearthly city of Tenochtitlán fell under the heels of conquerors. The canals were filled in. The city became known as Mexico City. As for Xochimilco, it is the last remnant of the original lakes—and one of the last habitats of the Xólotl.

I went to Mexico City twice for the dictionary. Each time, I went expecting that there would be some friction between members of the team, especially as the stakes rose when the job neared its completion. When I mentioned such a concern to Ximena, she just laughed. And she was right to laugh it off. Never was there heard a discouraging word in my presence at least. The headquarters of the Control Bureau was in a building—perhaps a former carriage house or servants’ quarters—within the walled yard of a substantial house in Coyoacán—a district of Mexico City (in fact, I am currently halfway through reading The Savage Detectives—a book saturated with the love of reading and writing by Roberto Bolano. Much of the beginning of that book takes place on a similar property in Coyoacán—making it easy for me to imagine being there). Rika and I and the Control Bureau team ate one meal of molé, and other traditional Mexican dishes, in the main house. Back in the Control Bureau, things hummed with energy and purpose, and harmony. Music was always playing. I heard some beautiful Mexican guitar music, ineffably sad, that I have regretted a thousand times I didn’t ask for a copy of. It seemed both completely natural and entirely dubious that such a huge project was being orchestrated under our noses. Even harder for me to believe was that the dozens of artists who contributed art to the book did so at no cost. I cannot imagine artists volunteering their work in such great volume in a city in the United States.

The editors shut the DICTIONARY ABCDF off at 1500 pages, which was pretty much its physical limit. Of that boundary, boundless Cristina said in her introduction: “Nevertheless we are still obsessed by the multiple allusions that we find every day.” I know how it is. Once one is on to something, it is hard to turn the spigot off. But wisely, she did.

The book, when it appeared, was a magnificent as it had been conceived to be. I don’t think more than a handful of printers in the world could have pulled off what Rika and Mr. Takahashi and the rest of Toppan Tokyo did. We even made the flip lens for the carton (images of the volcanoes), using Toppan’s proprietary lens technology, in our own factory. The book was monstrously heavy, and yet bound so well that it seemed as solid as a new Volkswagen bug. The book caused what could accurately be called a stir in Mexico City. An exhibition was organized at the Palacio de Bellas Artes. Proceeds from the sale of the book were donated to a fund to help street children. It truly was an influential work. It even made it into Phaidon’s The Photobook 2 as one of the best photo books of all time.

What did I take away from the experience that had a bearing on A Journey Through Literary America? Simple:

1) The notion that one could have a dream for a book, assemble some friends, and carry it out.

2) I had the opportunity to witness, in another country and context, the power of the meaning of place.

On the second to last page of the remarkable dictionary there is a litany of numbers–a Harper’s-like list–that I had never noticed until today. Among its revelations:

35,907 hours were spent

569,750 kilometers were traveled

22,335 images were examined to select the material, of which 1,556 were chosen

3,120 cups of coffee were imbibed

2,520 packs of cigarettes were consumed

4,600 tortillas were consumed

169 friendships were gained, and none were lost.

As time has gone on, this last statistic has had to be revised, I fear. (I speak from personal experience). One wishes sometimes for a neoteny of friendship. It is as painful to lose some friends as it is to lose one’s youth. But I will never forget those heady times, nor the lessons I learned, nor the solidarity of all of us who were working towards such a magnificent goal. TRH