It is now August 12th. In less than two months, my wife and son and I will be hitting the road in a one-way Budget SUV rental, headed from Santa Monica, California to Boston, Massachusetts. It will be a reverse journey in terms of the history of American literature: the California coast that became a symbol of promise—of sunshine and well-defined noirish shadows—backwards through Salt Lake City—the location that Brigham Young declared was “the right place” for his band of followers in 1847, eastward over the Rockies, through the prairies and past the isohyetal line of rainfall that defines the American Desert, back through the settlements of farms and white houses of Illinois and Ohio. A stop along the way will be Cooperstown, New York, founded by the father of James Fenimore Cooper—once the greatest “painter” in words of the American landscape. Then we will pass through the Berkshires of Massachusetts (once home to Melville and Hawthorne) on the way to Boston and to Concord, where the first shots of the Revolutionary War had been fired, and the first blood spilled, before Emerson, Hawthorne, Thoreau and Alcott made it their home.

As preparation, I have been reading a book I once read in paperback, in my teens: Blue Highways, by William Least Heat Moon, copyright 1982. Least Heat Moon, half Native American (they were called Indians in those days), leans against a cane on the back jacket of the 9th printing that I borrowed from the library, a short-looking man with a thick head of hair, a pair of suspenders, and a soulful look in his level gaze. If I am right about his stature, it probably served him well for the long journey he took. After losing his job and, to some degree, his wife, he got in a van he named “Ghost Dancing” and drove around the country, sleeping in the van most nights.

“Bust” of William Least Heat Moon

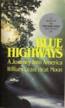

William Least Heat Moon he explained the source of the book’s title thus:

“On the old highway maps of America, the main routes were red and the back rods blue. Now even the colors are changing. But in those brevities just before dawn and a little after dusk—times neither day nor night—the old roads return to the sky some of its color. Then, in truth, they carry a mysterious cast of blue, and it’s that time when the pull of the blue highway is strongest, when the open road is a beckoning, a strangeness, a place where a man can lose itself.”

Detail of 1960 road map, with blue highways.

The above passage is typical of Blue Highways. Well-wr0ught, with a sense of rhythm and depth that suggest miles on the highway spent working out the sentences. Least Heat Moon’s observations, I am pleased to say, remain as trenchant as they did when I first read them.

This is the cover of the bestselling paperback I read in my youth

The text has aged well. Sadly, I bet 90% to 95% of the people he profiled along the road—venerable American men and women who were denizens of the blue highways—have passed away.

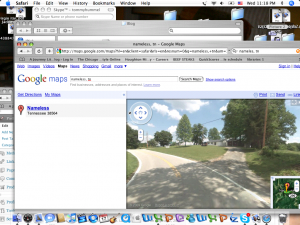

The atlas I have been consulting for our own travels is “The Mapquest Atlas,” copyright MMIIV, it says (a Roman numeral which doesn’t exist, I think) which I got for free with a book club offer. It is from back in the days when Mapquest was in its ascendancy and Google was perhaps nothing yet but a twinkle in is founders’ eyes. I felt bad obtaining it, with its jaunty Mapquest logo, even though it was free. Road atlases, it seemed to me, were the proper domain of Rand McNally. In my Mapquest atlas, the interstates are blue, with narrow white lines in the middle like a digestive tract, and the blue highways of the past are red or orange or nonexistent. Even when he made his jaunt, it seems like half the towns he visited out of curiosity, towns such as Liberty Bond or Moonax, Oregon, had already vanished from anything but his map. Towns like Nameless, Tennessee had ninety residents and a general store. Nameless has not been effaced. I can call it up on Google maps. The so-called”street view,” shows a bend in the road and the driveway of an unidentified house which seems to be in some other township though.

Blue Highways is great for stirring the traveling blood. And it is useful for travel tips, though I don’t know how well the following one has aged: according to the author, the best kinds of cafe are the ones with the most calendars.

No calendar: Same as an interstate pit stop.

One calendar: Preprocessed food assembled in New Jersey.

Two calendars: Only if fish trophies present.

Three calendars: Can’t miss on the farm-boy breakfast.

Four calendars: try the ho-made pie too.

Five calendars: Keep it under your hat, or they’ll franchise.

Unfortunately, that is one my little family may have difficulty putting to the test. With an eighteen month-old son, and a limited window of time, we’ll need to keep mostly to the interstates, which generally preclude eating establishments of an original nature. But it is a trip, and a trip all the way across the country, and nothing can take away the epic nature of that.

Book Update: due to a paginating error, what I thought would be a rubber stamp of approval on the plotter proofs turned into another wait for a new set of plotter proofs to be made. I won’t belabor the details of what exactly happened. The lesson learned is that not everything in printing can be anticipated, not even if one has been in the business for over a decade. Tune in again in a few days and I hope you will read that A Journey Through Literary America has gone to press.